|

Mt. Rainier (5)

|

|

| Last Updated 11/30/03 | |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Climb Description |

|

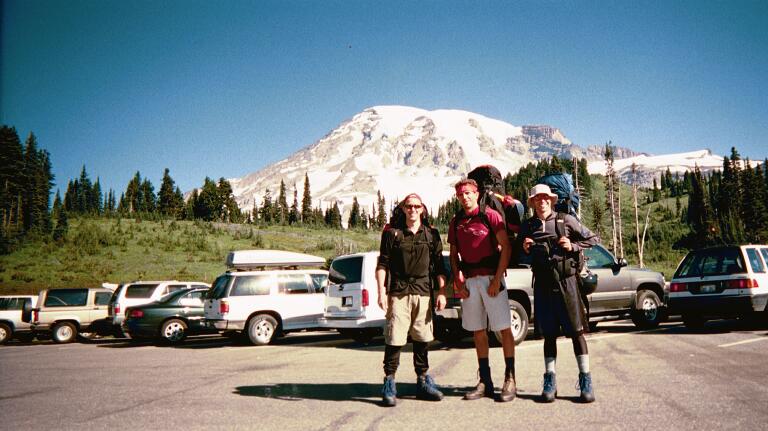

A couple of friends: Scott, Seth and I, headed over to Rainier on Friday after work. We slept on the side of the road for a few hours on the way, and got to Paradise around 7:30 Saturday morning. After securing our climbing permit and loading our packs, we stopped in the lodge for the breakfast buffet where we met three other friends Kevin, Jen and Bruce. After breakfast, we threw on our packs and started up. The climb to Camp Muir was rather uneventful, so let me take this time to provide a little back-info on my climbing partners.

Seth: A Minnesota kid (he's 25), has been working as an engineer in my office for a couple of years. I took Seth for his first skydive two years ago (well, actually he jumped with a tandem instructor and I just flew along side them). He liked it so much, he went for his second jump last summer (again, I jumped along side) and he was the only one of my friends that was lucky enough to experience a malfunction and actually get to use the reserve parachute. Anyway, he has never been climbing before and went out last week and spent around $500 in equipment (pack, boots, pants etc) to get ready for this climb. For the last week he'd been having stomach problems and I was beginning to worry that he wouldn't have the strength to climb. On Thursday he went down to the heath center where they gave him some medicine to keep him from puking after eating, and drew some blood for tests . But they had trouble with the needles and ended up letting some blood infiltrate into his arm. Anyway, that sounds far from the topic I started with, but it comes up again later.

Kevin: Kevin started work at Micron about two years ago as a recruiter. He is a big time rock and ice climber. He started asking around as soon as he got here looking for climbing partners and someone introduced him to me. But we never got around to climbing together until now. He came on the Salmon raft trip with us last month and was a real hoot to have around. He brought one of those competition kites on the river and we had a blast flying it on the beaches. It flies so much like a parachute I was able to get the knack right away even though it practically lifted me off the ground. (I did digress that time, oops).

Jen: Jen is Kevin's chum. She came on the Salmon River raft trip with us and has been trying like crazy to get into climbing. Her, Bruce and Kevin climbed Mt. Adams along a fairly easy route (is there such a thing at 12,000 feet?), which was her first high summit. She said that she climbed rather slowly and it wasn't clear as to whether or not she would make an attempt at the summit of Rainier or not.

Bruce: One of Kevin's climbing buddies. This was the first time I'd met Bruce. Kevin and Bruce go way back and have done a lot of ice climbs and back packing. In fact, they have done every Grand Canyon route that I've done and many more. Bruce's license plate is BAKPKR or something like that. Kevin and Bruce have each made a couple of attempts at Rainier, but between weather and altitude sickness, hadn't gotten within 3,000 feet of the summit.

Along the way, we watched as an Chinook helicopter flew in and hovered over Camp Hazard at the tip of the Kualtz glacier, apparently extracting a climber. We would find out later that a climber had come down with a case of HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema). HAPE is a very rare but very dangerous form of altitude sickness. The blood becomes thin and for some reason it begins to seep into the lungs, filling them with blood and suffocating the victim. The only thing worse is HACE (High Altitude Cerebral Edema) where the brain begins to bleed, causing such high cranial pressure that the victim looses all rationality and or consciousness. If not treated, both are fatal. Later on, the helicopter returned to Camp Hazard for another extraction, but we never found out what the second trip was for.

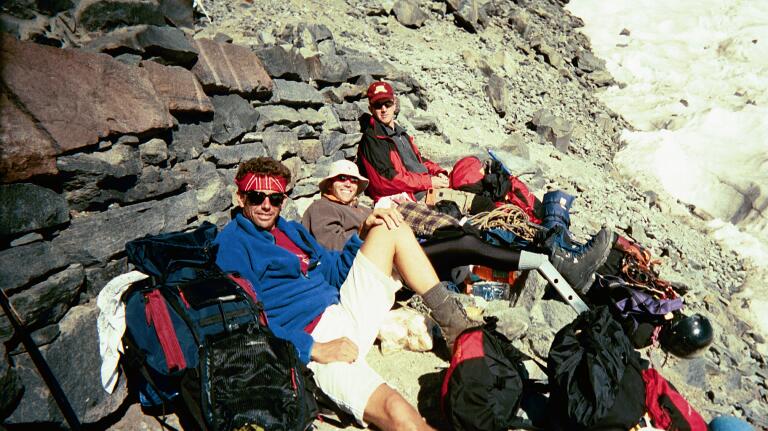

We reached Camp Muir (10k feet) at 16:00. We didn't set up camp, but brought out the stove and cooked up some Cajun Rice & beans and wrapped them in tortias for lunch. Then we just basked in the sun and snoozed for a couple of hours. Kevin, Jen and Bruce showed up around 19:30 and set up their camp. Just after that, my team ate another scrumptious dinner (I had sweet-n-sour chicken... yum yum), then at 21:30 we roped up, head lamps a-blazing and headed out across Cowlitz glacier.

So with that, at 01:00, Scott and I headed out to finish off the last 3,000 feet to the top. The usual route traverses the Ingraham glacier to the base of Disappointment Cleaver, but I had called about route conditions earlier in the week and they said that the Ingraham Head wall was still climbable. So we had planned on climbing to the wye in the trail and make our final decision there about which variation to take. Only two teams of climbers had left Ingraham Flats before us; we passed one team who was having trouble finding the route shortly after leaving camp. They were contemplating heading out across the glacier on their own in search of the D.C. route, but elected to follow us instead. Once across Ingraham glacier, there was no sign of the expected wye in the route (one way going to the head wall, one going to the D.C.). After passing the point at which the Cleaver route should have pealed off, we realized that the decision had made itself, and we would be climbing the head wall.

The Ingraham glacier flows down from the summit dome and slips through the narrow passage between Disappointment Cleaver and Gibraltar Rock. This bottle neck (the Ingraham Head Wall) usually (especially at this time of year) results in a massive ice fall that make the route impassable by weekend mountaineers. But this year, the lay of the ice permitted a straightforward and climbable route even for the likes of us. We snaked our way through the mess of séracs (huge blocks of ice) and around the ends of gaping crevasses until we reached a series of switchbacks. Here in the switchbacks, we were passed by a team of three climbers who were setting a very fast pace to the top.

At the top of the switchbacks, we rested a while and took in the night. The moon had set on the camp below and we could see a dozen tents glowing from the inside as climbers began preparing for their assault on the mountain. We were feeling good that we had gotten such a big head start on the crowd, as we replaced the batteries in our own head lamps. We looked for the team that had been following us, but there was no sign of them. We assumed that they had found the D.C. cut off, or that they were at least in search of it. We never saw them again. From the top of D.C. the route serpentined around a few crevasses then topped out on an Eastward sloping shoulder. From there we could see, way off in the distance across the Emmons glacier, along a very long traverse , the headlamps from the team who had passed us in the Ingraham switchbacks as they disappeared around another distant mountain shoulder. We headed out along easy hiking until the side slope we were traversing began to steepen. Soon we found ourselves stabbing our ice axes into the wall over our heads for balance, while the slope below had been replaced by a fifty foot vertical cliff. The base of the cliff below ended in a short steep slope that funneled down to a gaping crevasse. A fall here would surely have had a disastrous outcome. We moved cautiously along the ledge, which continued to shrink until it was not much wider than the width of our boots. We rounded a corner and the trail finally widened out again, then we crossed a narrow snow bridge before we were back onto less hazardous slopes.

The route continued it's upward traverse across the Emmons glacier, while the wind continued to get colder and stronger. The eastern horizon began to turn pink, then red as the day's first light gnawed away at the utility of our headlamps. Scott, who had been having trouble keeping his harness from sliding down while climbing, stopped more and more frequently to make adjustments as we finally reached the end of the first leg of the long traverse. We turned south and worked our way on an upward traverse back around to the east, just below the summit slopes. The wind was so cold I was beginning to shiver every time Scott stopped to make harness adjustments. I considered putting on a few more layers of cloths, but they would have to go on under my outer shell, and I didn't want to take that off even for a few seconds. I figured I would be better off putting up with the cold until we reached the shelter of the summit crater.

We crossed another snow bridge and at 07:30 we were standing on the crater's rock rim. The crater was (as always) filled with snow, making a relatively flat area large enough to accommodate several football fields. This is quite striking after seeing nothing but ice falls, crevasses and steep slopes for the last two days. Below the snow plateau, lie hundreds of volcanic steam vents who's warmth create hidden snow caves that snake their way to the edges of the snow field and open up creating large moats between the snow and the rock rim. We found a fairly thin snow bridge between moats, made a quick, light, crossing and we were standing on the crater's snow floor. The summit lie on the rim, directly across the crater. The leader of the switchback team, was explaining to his partners that there was no need to cross the crater, that they had made it to the top. I didn't say anything about the registry that lies below the rocks near the summit. Most people who do all the work to climb that far, are willing to walk the extra quarter mile to sign the registry. I knew Scott was hearing their leader's rationalizations, and I wasn't sure if he wanted to continue or not. But without a word, he dropped off his pack and started gathering the few items of food and water that we would want to take with us. I was relieved that I didn't have to find the strength to make that decision. I took off my shell, and put on all the clothes I had, then stuffed my pockets with Jelly Bellies, water and snacks. We unroped, trudged across the crater and flopped down next to the registry were we signed, rested and ate. We made it.

We didn't stay long. We were anxious to make it back across the snow ledge

before the sun had time to soften it, so we headed back across the crater and

after tying Scott's harness up with some string, we roped up and at 08:30 we

started our decent. The trip back across the long traverse was quick, and

without too much notice the wind had died down. By the time we made it back to

the ledge, it was time to shed some clothes. There were a couple of teams right

on our heels, so we decide to let them cross the ledge first just to test it

out, and extended our break for several minutes. After letting the other

teams pass, we crossed the snow bridge and made our way to the ledge. Someone

had set up a running belay at each end of the ledge, so we took advantage and

clipped in for the crossing. The snow was much softer, but we passed with no

problem. We had decided earlier that we would try again to find the D.C.

route for the decent, but there was no clear route leading in that direction

from the top. We caught up to the "test team" at the top of the Ingraham Head

Wall and had a conversation with the girl leading the group. It turned out that

she was a guide on the mountain and had been working this route for the last

five years. She said nobody was taking the D.C. route yet because

The test team packed up and headed down, but one guy that we thought was in their group was left stranded. We stayed to find out what his story was, and it turned out that he was with another group that left him their on their way up earlier that morning. He had been experiencing leg cramps on the way up from Ingraham Flats and decided he couldn't make it any farther. His group couldn't take him with them, but he couldn't go back through the head wall alone so they set him up with a tarp, a book some sun screen and a CD player. He had been there for five hours and was getting pretty bored. He said he had climbed Kilimanjaro only a month before and didn't have any trouble with that, but the guide he was with on this trip was pushing the group too fast and causing his cramps. We gave our sympathy and left.

At around midnight, Kevin and Bruce headed out of camp, but we didn't hear a peep. We didn't climb back out of our tent until the sun hit it the next morning. We got up, and started cooking water for breakfast. It wasn't much later that we saw two climbers down-climbing the Head Wall. We knew that if this was Kevin and Bruce, they weren't gone long enough so they had to have turned back short of the summit. We watched and waited. We weren't able to identify them until they were nearly back to camp and were a bit saddened when we saw that it was them. They said they made it to within 700 feet of the top, but turned back when Bruce began to have trouble making headway. He was taking about five minutes to take five steps and even though there was no wind, Kevin was getting so cold he thought he felt signs of hypothermia setting in, so he turned the duo back. Kevin vowed to return later this year to complete the climb. A short time later, another team of four climbers made their way back down the mountain to camp. They too had turned around short of the summit, close to the place Kevin and Bruce turned back.

We through everything back on our backs and half trotted, half slid our way back to Paradise, where we met up with Kevin's crew again. We were all feeling much better after showering and beginning the process of re-hydrating. We caravanned to Yakima were we wolfed down pizza and more liquids. Even though we all didn't summit, everyone felt the trip was a complete success, and there was a lot of laughing and joking as we recounted the events of the trip. Then we piled back into the trucks and headed back to Boise.

|

Scott: Another kid (25) from Montana. Scott also works as an engineer in my

office, and his claim to fame comes from the swimming world. He has won many

awards for several different swimming events. In fact, his best personal time in

the sprint, still beats the fastest women's world record!

Scott: Another kid (25) from Montana. Scott also works as an engineer in my

office, and his claim to fame comes from the swimming world. He has won many

awards for several different swimming events. In fact, his best personal time in

the sprint, still beats the fastest women's world record!  Okay, back to the climb: My team (me, Seth and Scott) set a pretty good pace

on the way to Camp Muir, but Seth soon began to complain about back trouble. We

made some major adjustments to the fit on his backpack (remember it was a new

pack?) and that seemed to do the trick. A couple of hours later though, his left

arm began to go numb (remember the arm?). We thought it was just more pack

trouble and tried making small adjustments and kept going.

Okay, back to the climb: My team (me, Seth and Scott) set a pretty good pace

on the way to Camp Muir, but Seth soon began to complain about back trouble. We

made some major adjustments to the fit on his backpack (remember it was a new

pack?) and that seemed to do the trick. A couple of hours later though, his left

arm began to go numb (remember the arm?). We thought it was just more pack

trouble and tried making small adjustments and kept going.

The climb to Ingraham flats (11,600 feet) took about two hours and proved

that the new guys had good rope sense. Everything looked good, the weather was

perfect and we were full of energy. We set up the tent and began dumping

everything from our packs that we wouldn't need for a summit attempt. Then Seth

informed us that the numbness in his arm had turned to weakness. He had made the

decision that he would not take a shot at the summit. Looking at his arm, we

could see the bruised area of the infiltrated blood that started out around the

needle stab, had worked it's way all the way down to his wrist, with big

splotchy patches mixed in. We didn't argue with him about staying back. He would

never be able to arrest a fall with one arm.

The climb to Ingraham flats (11,600 feet) took about two hours and proved

that the new guys had good rope sense. Everything looked good, the weather was

perfect and we were full of energy. We set up the tent and began dumping

everything from our packs that we wouldn't need for a summit attempt. Then Seth

informed us that the numbness in his arm had turned to weakness. He had made the

decision that he would not take a shot at the summit. Looking at his arm, we

could see the bruised area of the infiltrated blood that started out around the

needle stab, had worked it's way all the way down to his wrist, with big

splotchy patches mixed in. We didn't argue with him about staying back. He would

never be able to arrest a fall with one arm.  We finally came to the end of the second leg of the big traverse. We could

see a small pile of rocks only a few hundred feet above; we knew they were part

of the crater rim and that we were near our goal. We started up a series of

switchbacks and soon came across the three who had passed us on the Inghraham

switchbacks. The middle climber was looking pretty bad. We had passed multiple

places along the way were people had stopped to review their dinner menu from

the day before, and this guy looked like he was one of them. Soon, we were

within a hundred feet of the crater rim, and made one more stop to rest and make

adjustments. The switchback guys were making their last pitch and passed us

again. Everyone was spent, but knowing the rim was right there shortened the

"rest" in everyone's "rest step".

We finally came to the end of the second leg of the big traverse. We could

see a small pile of rocks only a few hundred feet above; we knew they were part

of the crater rim and that we were near our goal. We started up a series of

switchbacks and soon came across the three who had passed us on the Inghraham

switchbacks. The middle climber was looking pretty bad. We had passed multiple

places along the way were people had stopped to review their dinner menu from

the day before, and this guy looked like he was one of them. Soon, we were

within a hundred feet of the crater rim, and made one more stop to rest and make

adjustments. The switchback guys were making their last pitch and passed us

again. Everyone was spent, but knowing the rim was right there shortened the

"rest" in everyone's "rest step". the head wall

was still in such good shape, and it cut off an hour from the trip. So we

decided to go down the same way we came up and skip the D.C all together.

the head wall

was still in such good shape, and it cut off an hour from the trip. So we

decided to go down the same way we came up and skip the D.C all together. The route through the head wall was warming up, and we could hear ice and

rock fall from both Gibraltar and the Cleaver. We moved as fast as we could

without sacrificing our balance too much. By the time we made it to the

relatively flat-scape of Ingraham glacier, we were drenched with sweat, but

relieved. A short time later, we worked our way around the ends of the last

crevasses on the glacier and walked into camp at 12:00 sharp. We dropped our

gear, moved the tent to a flat spot and crashed. While we were climbing,

Kevin's team had moved their camp up to Ingraham Flats and were set up only a

few feet from us. By the time we surfaced, Kevin and Bruce were preparing gear

for their summit bid. Jen had decided to stay behind because she didn't want to

jeopardize Kevin's chance at bagging the summit. This would be his fourth try at

it. Seth cooked some chow and we visited with other climbers for a few hours and

were back in bed for the night by 17:00.

The route through the head wall was warming up, and we could hear ice and

rock fall from both Gibraltar and the Cleaver. We moved as fast as we could

without sacrificing our balance too much. By the time we made it to the

relatively flat-scape of Ingraham glacier, we were drenched with sweat, but

relieved. A short time later, we worked our way around the ends of the last

crevasses on the glacier and walked into camp at 12:00 sharp. We dropped our

gear, moved the tent to a flat spot and crashed. While we were climbing,

Kevin's team had moved their camp up to Ingraham Flats and were set up only a

few feet from us. By the time we surfaced, Kevin and Bruce were preparing gear

for their summit bid. Jen had decided to stay behind because she didn't want to

jeopardize Kevin's chance at bagging the summit. This would be his fourth try at

it. Seth cooked some chow and we visited with other climbers for a few hours and

were back in bed for the night by 17:00.

We ate bagels with PB&J for breakfast and packed up. Jen had been working on

packing their camp and the three of them were packed up and started hiking out

just before us. We stopped for some photo ops and made it back to Camp Muir just

as the other three were leaving for Paradise. We stayed for forty-five minutes

or so, repacking our packs and using the crapper. There was a service

helicopter making round trips between Muir and somewhere below, as the summer

project was to build another out house and remove some of the trash that had

accumulated there. There was another team nearby who was recouping from their

climb. They turned out to be yet another team that was beaten by the mountain.

One guy said he tossed his cookies at least five times before giving up.

We ate bagels with PB&J for breakfast and packed up. Jen had been working on

packing their camp and the three of them were packed up and started hiking out

just before us. We stopped for some photo ops and made it back to Camp Muir just

as the other three were leaving for Paradise. We stayed for forty-five minutes

or so, repacking our packs and using the crapper. There was a service

helicopter making round trips between Muir and somewhere below, as the summer

project was to build another out house and remove some of the trash that had

accumulated there. There was another team nearby who was recouping from their

climb. They turned out to be yet another team that was beaten by the mountain.

One guy said he tossed his cookies at least five times before giving up.